This is our last, but not at all the least, important heritage blog we will be publishing for 2022. This concludes our 7-part series, “Celebrating Diversity in Southern Vermont”. If you haven’t been following the series or missed any of the previous blog posts, please visit Heritage — Manchester Vermont for a complete list.

U.S. History

So why do states celebrate Native American Heritage Month in November? The efforts began at the turn of the century to gain, at minimum, a day of recognition for the significant contributions the first Americans made to the U.S., both in its establishment and growth. It began in Rochester, NY with Dr. Arthur C. Parker, a Seneca Indian, who was the director of the Museum of Arts and Science in Rochester. He persuaded the Boy Scouts of America to set aside a day for the First Americans, and for three years, they adopted this day. In 1915, the annual Congress of the American Indian Association directed its president, Rev. Sherman Coolidge, an Arapahoe, to call upon the entire U.S. to observe such a day. It was Coolidge who issued a proclamation on Sept. 28, 1915, declaring the second Saturday of each May as an American Indian Day and within this appeal, the first formal recognition of Indians as U.S. citizens.

The year leading up to the proclamation, Rev Red Fox James, a Blackfoot Indian, rode horseback from state to state with a proposal for a national holiday in commemoration of the North American Indian. In total he traveled more than 4,000 miles in 9 months and on December 14, 1915, he presented endorsements from 24 state governments to the White House. While such a national holiday commemorating Native Americans was not established at the time, a few states subsequently created their own versions of that day. The first of these states was New York, which began officially celebrating American Indian Day in 1916.

Fast forward 60 years and in 1976, S.J. Res. 209 authorized President Gerald Ford to proclaim October 10-16 as Native American Awareness Week. Ten years later, Congress passed S.J. Res. 390, requesting that the president designate November 23–30, 1986, as American Indian Week. Congress continued this practice in subsequent years, declaring one week during the autumn months as Native American Indian Heritage Week.

In 1990, Congress passed, and President George H. W. Bush signed into law, a joint resolution designating the month of November as the first National American Indian Heritage Month (also known as Native American Indian Month). “American Indians were the original inhabitants of the lands that now constitute the United States of America,” noted H.J. Res. 577. “Native American Indians have made an essential and unique contribution to our Nation and to the world.” The joint resolution stated that “the President is authorized and requested to issue a proclamation calling upon Federal, State, and local governments, interested groups and organizations, and the people of the United States to observe the month with appropriate programs, ceremonies, and activities.” In 2008, the language was amended to include the contributions of Alaskan Natives. Every year, by statute and/or presidential proclamation, the month of November is recognized as National Native American Heritage Month.

Other notable dates celebrating Native American heritage and their contributions are: Native American Day – falling on the fourth Friday of September each year and Indigenous Peoples Day – a.k.a. First Americans Day, falling on the second Monday of October each year.

Vermont’s History

It is well known that Native Americans lived and thrived in all parts of New England for the past 13,000 years, but it is only since 2011 that the State of Vermont officially recognized The Elnu Abenaki Tribe, The Nulhegan Abenaki Tribe, The Koasek Traditional Band of the Koas Abenaki Nation, and the Abenaki Nation at Missisquoi.

Don Stevens, chief of the Nulhegan Band of the Coosuk Abenaki Nation, has been quoted as saying, “We are the Nulhegan Tribe; the Memphremagog Band; the Northern Cowasuk Indians. We have lived here from time beyond memory. Our memories and oral history tell about when the old ones were faced with the decision to stay or travel west to the Great Lakes. Some made the journey, and some stayed here in N’dakinna (our homeland). Our oral history tells of the wars and the hardships of survival and acceptance in the centuries after. Our presence here has not always been wanted, warranted, or even admitted.”

The ‘Great Puritan Lie’

“I call it the Great Puritan Lie,” says Chief Roger Longtoe Sheehan, of the Elnu Abenaki. “Basically, the Puritans came in, wanted more land, north of Massachusetts, and went over to the king,” Sheehan says. “And he said, ‘Well, what about my loyal native subjects?’ And they just said, ‘Oh, well nobody really lives there. They just come down here and hunt and fish and then like seem to go away at night or something.’” Flat out denial that there was a permanent Native American presence in this region.

Eugene Rich, the co-chair of the Missisquoi Abenaki Tribal Council, says, “there’s never been a time when this tribe wasn’t here. There is a time period in which we weren’t talked about. We didn’t talk about ourselves. And people forget.” Here, Rich is alluding to the second reason that it’s a big deal that the Abenaki are still here. Starting in the 1930s, they were targeted by Vermont’s eugenics program: “Breeding Better Vermonters”

This was a very dark chapter in Vermont’s and the nation’s history. It involved coerced sterilization of the Abenaki — also French Canadians, poor people, and disabled people. According to Nancy Gallagher, the author of the book Breeding Better Vermonters: The Eugenics Project in the Green Mountain State, the sterilizations plateaued around World War II, but by some accounts, they went on for much longer.

Don Stevens, chief of the Nulhegan Band of the Coosuk Abenaki Nation, says what happened is still impacting the Abenaki psyche. “My grandmother was on the survey,” Stevens says. “She changed her name three times. She was born as Lillian May, married as Pauline, and died as Delia, because she was trying to avert the survey,” he says. “And she died in the ’90s. I mean, it’s not that far away. So, there’s still a lot of people that don’t want to be on a list, if you know what I mean.”

For centuries there was denial of the Abenaki’s presence, and then persecution with eugenics. About six years ago, however, a change occurred. Then, Democratic Gov. Peter Shumlin, proclaimed Columbus Day as Indigenous People’s Day by executive order. And in April 2019, Vermont passed a bill permanently abolishing Columbus Day in favor of Indigenous Peoples’ Day joining a small handful of states who had passed similar legislation.

The steps taken to acknowledge to celebrate and acknowledge our FIRST Americans, the Native Americans is great but long overdue. The Nation, the State of Vermont, and its residents continue to make great strides in recognizing the value and contributions of the Native Americans in our country and communities, but there is still work to be done. Working together with open hearts and minds, creating equal opportunities for all, engaging in open dialogue, continued education, and addressing racist actions and behaviors, no matter how uncomfortable it makes us, will allow progress, equal protection, and positive change.

Celebrating Local Leaders in Southern Vermont

Rich Holschuh is a Windham County resident (Wantastegok/Brattleboro, VT) of Mi’kmaq and European heritage and an indigenous cultural researcher. He serves on the Vermont Commission for Native American Affairs and as a public liaison for the Elnu Abenaki Tribe, representing with governmental agencies of oversight such as the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), and the Vermont State Department of Historic Preservation (DHP). He also interfaces with other tribal groups, corporate entities, other local and state agencies, civic groups, and public and private educational institutions, providing outreach and building connections.

Mountain Names: Remembering their Aboriginal Origins – Green Mountain Club

In our research, we came across an interview with Rich by VPR’s “a Brave Little State” segment back in 2019. At one stage in the interview, Rich and the reporter walk through a local Brattleboro Cemetery, through the rows of headstones, and Rich stops at particular grave. The grave of a man named Col. John Sergeant, a military commander who died in 1798. The gravestone epitaph stated: “Col. John Sergeant…Who now lies in the same town he was born. And is the first person born in the State of Vermont.” Rich is quoted as then saying “The story is here, but it’s been hidden. The Abenaki people, who were basically written out of the story, are still here.” If you let that sink in, you can quickly realize what is being said. They are purposively denying the existence of the Native Americans who were born, lived and died here before any puritan settler ever stepped foot in the State of Vermont

It should also be noted that Rich Holschuh is a member of the Vermont Commission on Native American Affairs, and it’s thanks to his efforts that Democratic Gov. Peter Shumlin proclaimed Columbus Day as Indigenous People’s Day in 2016. He wants people to remember that the Abenaki have been in this region for 12,000 years. In other words, just a few of them were born here before Col. John Sergeant.

Celebrating Diversity through the Arts:

Southern Vermont Arts Center – Many America’s Exhibition

Inspired by Ronald Takaki’s A Different Mirror, the Many Americas exhibition and public programming takes as a premise that we do not share a common history and our divergent histories are the source of our troubled civic discourse. Each of the artworks in the exhibition uses history as their point of departure and speaks to present day issues. The artworks demonstrate the multiple, sometimes competing histories of America. The exhibition will feature approximately two dozen artworks and installations and a variety of audience engagement approaches including texts, guided tours, and programs that draw out the issues raised by the artwork. In doing this, we seek to demonstrate how an art museum can become a public square where people can come together and talk about important civic issues.

In particular, Michael Ryder (Ojibwe) presents a contemporary dream catcher that uses personal archive of historical photographs to talk about bodily trauma and to highlight the displacement of native people

Ryder, an interdisciplinary artist whose work revolves around themes of community, childhood adversity, memory, and the fermentation of generational trauma through adulthood creates work that “seeks understanding of himself, his family, his heritage, and the systems that connect us to our communal bonds.” In The Deconstruction of the Father, Ryder populates a contemporary Ojibwe dreamcatcher with material from his personal archive to reflect on the trauma of indigenous displacement.

In Anishinaabe culture, the dreamcatcher is a handmade, woven sinew net set on a hoop of willow that is decorated with sacred items such as feathers or beads and placed above one’s bed for protection. The dreamcatcher catches any harm that may be in the air thus protecting the sleeper.

Native Languages of the Americas, a non-profit organization focused on “preserving and promoting American Indian languages described dreamcatchers:

“Dreamcatchers are an authentic American Indian tradition, from the Ojibway (Chippewa) tribe. Ojibway people would tie sinew strands in a web around a small round or tear-shaped frame—in a somewhat similar pattern to how they tied webbing for their snowshoes—and hang this “dream-catcher” as a charm to protect sleeping children from nightmares. The legend is that the bad dreams will get caught in the dreamcatcher’s web. Traditionally, Native American dreamcatchers are small (only a few inches across) and made of bent wood and sinew string with a feather hanging from the netting, but wrapping the frame in leather is also pretty common, and today you’ll often see dreamcatchers made with sturdier string meant to last longer and decorated with beaded thongs. During the pan-Indian movement in the 60s and 70s, Ojibway dreamcatchers started to get popular in other Native American tribes, even those in disparate places like the Cherokee, Lakota, and Navajo. So, dreamcatchers aren’t traditional in most Indian cultures, per se, but they’re sort of neo-traditional, like frybread. Today you see them hanging in lots of places other than a child’s cradleboard or nursery, like the living room or your rearview mirror. Some Indians think dreamcatchers are a sweet and loving little tradition, others consider them a symbol of native unity, and still others think of them as sort of the Indian equivalent of a tacky plastic Jesus hanging in your truck.”

Celebrating Native American representation in EDUCATION

Bennington College

Traditional Music of North America is a full-term course offered by Professor John Kirk at Bennington College. The class explores music from early Indigenous music right on up to present day practitioners. Some of the traditions studied and practiced includes: Native American, Inuit, Québecois, Appalachian, African-American, Irish, Scottish, British Isle traditions, Cajun, Blues, Gospel, Mariachi, and Conjunto music. Instrumental, dance, and ballad traditions are studied and researched, and experienced first-hand. The course is focused on expanding awareness of traditional folk music and dance forms from an historical viewpoint and learning these music and dance forms through direct, hands-on experience.

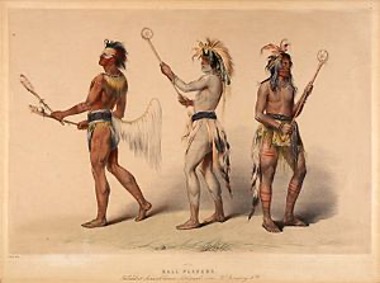

“Ball players”, a hand-colored lithograph by George Catlin

Celebrating Native American History of Sports

Originally called stickball, lacrosse began being played by the Algonquian tribe in the St. Lawrence Valley area. The event would bring hundreds, and sometimes even thousands of participants together. The simple rules called for players not to touch the ball with their hands, with no confining boundaries. As the sport matured, so did the equipment. What started as wooden balls, were later replaced by deerskin balls filled with fur, and their sticks would eventually be fashioned with nets made of deer sinews. It was French Jesuit, Jean de Brebeuf, who wrote about the game being played by the Huron Indians in 1636 and it was he who named the game “lacrosse”. And by 1860, lacrosse had become Canada’s national game. Today, lacrosse is played at many schools across the nation, including here in Manchester at Burr and Burton Academy. Next summer, be sure to catch a local lacrosse game if you have never been!

Celebrating our State, Regional, and Local Resources

The Wabanaki Confederacy is comprised of five principal nations: Abenaki, Malecite, Micmac, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot. There are four Vermont state-recognized Western Abenaki tribes:

The Elnu Abenaki Tribe

elnuabenakitribe.org – their traditional territory is Southern VT.

Elnu is an Abenaki Tribe based in Southern Vermont. Working to continue cultural heritage through historical research, lectures and school programs, oral storytelling, singing, dancing, and traditional craft making. Their primary focus is ensuring that their traditions carry on to their children. They are traditionalists trying to maintain their culture in a modern society. Learning from the past creates a better future for all.

The Koasek Traditional Band of the Koas Abenaki Nation –

koasekofthekoas.org – their traditional territories are Central and Northwestern NH and Northeastern and Central VT.

The Nulhegan Band of the Coosuk Abenaki Nation

abenakitribe.org – their traditional territories are the Upper Connecticut Basins of VT, Northern NH, and the eastern townships of Quebec.

The St. Francis-Sokoki Band of the Abenaki Nation of Missisquoi –

abenakination.com – their traditional territory is Northwestern VT.

Vermont Commission on Native American Affairs

State Recognized Tribes | Vermont Commission on Native American Affairs

Charged by law to recognize the historic and cultural contributions of Native Americans in Vermont, to protect and strengthen Native American heritage, and to address needs in state policy, programs, and actions. The Commission provides technical assistance on the application process for state recognition of Native American Indian tribes and reviews the documentation of applicants. The Commission develops policies and programs to benefit Vermont’s Native American Indian population.

For more history of indigenous peoples in Vermont, see:

- Calloway, Colin G. The Western Abenakis of Vermont, 1600–1800. The Civilization of the American Indian Series, v.197. This contains a chronology of the tribe and a good bibliography of sources.

- Haviland, William A. The Original Vermonters. This history includes information on the Abénaki and Mahican tribes in Vermont, an index, and a bibliography.

- Vermont Indians FHL book 970.1 D228v

- Joseph Bruchac, The Faithful Hunter: Abenaki Stories. Collected by storyteller Joseph Bruchac, these twelve Abenaki stories tell of life in ancient times. Old, sacred, and funny relations between the plants, trees, and animals weave for the reader a tapestry of Wabanaki values and insight. Included are many stories about Gluskabe, the “one who calls the Abenaki people his grandchildren.”

- Joseph Bruchac, The Wind Eagle and Other Abenaki Stories

(Greenfield Center, NY: Bowman Books, 1985). This is a collection of six Abenaki teaching tales. These tales were used to instruct young children, as well as to entertain. All of these stories are about the encounters of Gluskabe, the “one who calls the Abenaki people his grandchildren.” They reveal the beliefs of Vermont’s earliest peoples and their ties to their surroundings. - Colin Calloway, The Abenaki. This is a good research and reference tool providing a respectful overview of Abenaki history including culture, arts, wars, and beliefs from pre-European contact to the present day.

- Colin Calloway, Dawnland Encounters: Indians and Europeans in Northern New England

Students and adults searching for details of the Abenaki people will find a wealth of unbiased information from ancient history to present times. Heavy use of primary sources, including diaries, describes peaceful and antagonistic encounters with Europeans during colonial times. These sources also provide a sense of how the Abenaki managed to survive to today. - William A. Haviland and Marjory W. Power, The Original Vermonters: Native Inhabitants, Past and Present This book provides wonderful primary sources based on archeological findings that reveal how people lived in Vermont for at least ten thousand years before the Europeans arrived, and what has been their fate. This second edition contains thirteen additional years of research by archaeologists including vital new information on the origins of farming in Vermont.